"Squanto stayed with them and was their interpreter and was a

special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation."

-William Bradford

Governor of Plymouth Colony

The remarkable life story of the Patuxet Indian named Squanto

is reminiscent of the biblical saga of Joseph, who was sold by

his jealous brothers into slavery. As in the Old Testament story,

this victim of unforeseen circumstances rose above the forces of

adversity in his life to become a trusted advisor and loyal friend

to the early English settlers at Plymouth Colony.

Squanto's story begins in the year 1605, when he and four other Indians

were taken captive by Captain George Weymouth, who was exploring the

New England coast at the behest of Sir Ferdinando Gorges. The Indians

were taken to England, where they learned to speak English.

Squanto spent the next nine years in England where he was befriended

by Captain John Smith, recently of Virginia, who promised to one day

take Squanto back to his people. He did not have long to wait.

After Captain Smith received the command to go back

in 1614, Squanto was returned to his people as promised

at the place Smith named New Plymouth.

The commander of the other ship sailing with Smith's mapping

and exploring expedition was Captain Thomas Hunt. One day,

when Smith was about to lead an exploring party, he ordered

Hunt and his crew to stay behind to dry their catch of fish

and trade it for more profitable beaver pelts before

sailing back home again.

But the wily Captain Hunt had another idea in mind. As soon

as Captain Smith departed, he slipped back down the coast to Plymouth

where he lured twenty Patuxet Indians-including Squanto-aboard his ship

under the pretext of bartering with them. The unsuspecting Indians

were seized and clapped in irons. Then, sailing across the bay to

the outer edge of Cape Cod, Hunt captured seven members of

the Nauset Indian tribe and hightailed it out to sea.

Hunt's destination was Malaga, Spain a notorious slave-trading port.

There the wicked captain proceeded to auction off his captives,

receiving twenty pounds for each of them.

Most of Hunt's captives were bought by

Arab slave traders and shipped off to North Africa.

However, monks from a nearby monastery found out

what was happening and rushed over to the auction.

They bought the remaining Indians, including Squanto,

"to instruct them in the Christian faith."

Already God was setting the wheels in motion

for Squanto's eventual return to New England.

Squanto, however, did not stay long at the monastery.

He met an Englishman bound for London and left Spain

for England. There he met and joined the household of

a wealthy merchant name John Slanie. Squanto lived

on Slanie's estate until he embarked for New England

with Captain Dermer in 1619.

When Squanto stepped on the familiar shores of home again,

he was horrified to discover that a mysterious ailment had

taken the lives of every man, woman, and child in his tribe.

Nothing was left but skeletal remains and ruined dwellings.

In deep despair, he wandered aimlessly through the woods

and fields he had played in as a child, and where he had learned

to hunt wild game. He walked for miles towards the southeast

to Massasoit's camp because he had no other place to go.

The wise chieftain of the Wampanoag tribe took pity on the

lonely, grief-stricken warrior who seemed to have lost all

reason for living. That was until Samoset, a chief of the

Eastern Abenaki tribe, arrived with news of a small

colony of peaceful English families who had settled

at Patuxet, on the site of Squanto's old village.

Samoset told of how the settlers were struggling to survive there

and that it would not be long before they would starve to death.

As Squanto listened, he decided to return to Plymouth,

along with Samoset and chief Massasoit, who brought

all sixty of his warriors with him. Although the colorfully

painted warriors alarmed the settlers, chief Massasoit

became a good friend and ally of the Pilgrims and later

signed a peace treaty of mutual aid and assistance with

them which lasted forty years, until his death.

The early settlers of Plymouth Colony were equally

astonished by Samoset and Squanto, both of whom spoke

English! Squanto believed it was his God-given duty to help

these ignorant newcomers survive in the wilderness.

He brought the settlers handfuls of slippery eels, which the

Puritans found to be "fat and sweet" and delicious to eat!

Squanto took several young men from the colony with him

to the place where he had caught the eels and taught them

how to stamp the creatures out of the mud with their

bare feet and then catch them with their hands.

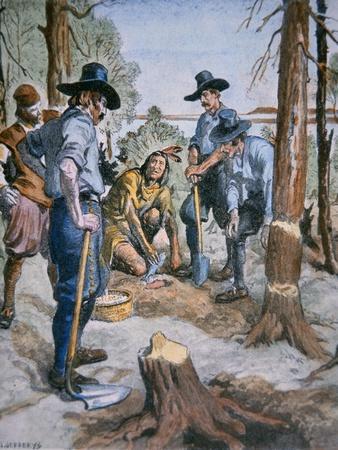

In the springtime, Squanto taught the Pilgrims how to

plant corn the Indian way, by burying fish with the kernels.

The fish was used to fertilize the newly tilled soil.

He also taught them how to make the weirs they would

need to catch fish. Obediently, they followed the

Indian's instructions and four days later the creeks

for miles around were clogged with alewives making

their spring run. The excited Pilgrims now had an

abundance of fish to feed their families and to

bury in their cornfields.

Squanto further taught the early settlers how to stalk deer,

plant pumpkins among the corn, draw sap from maple trees,

and to discern which wild plants were good to eat and were

good medicine, plus how to find all the best wild berries.

The Pilgrims began to see Squanto as a true godsend.

Through his advice and guidance they learned to

trap and trade beaver pelts, which were in great

demand throughout Europe, and which provided

them with a steady income in their new home.

Unfortunately, in November, 1622 while on a corn-trading

expedition to Indians on Cape Cod, Squanto suffered a nosebleed.

He told William Bradford, the Governor of Plymouth Colony,

that among the Indians this was a sign of imminent death.

He asked the governor to pray for him," that he might

go to the English man's God in Heaven". Several days

later, Squanto was dead. The Pilgrims, whom he had

selflessly helped begin productive lives in the New World,

deeply mourned the loss of their true and devoted friend.

Information source:

"The Light and The Glory"

(1977)

By Peter Marshall and David Manuel

Revell Publishing Company

Grand Rapids, Michigan

No comments:

Post a Comment